New research at The University of Manchester has found that over two-thirds of women runners across Greater Manchester and Merseyside have experienced abuse. This has taken the form of physical and sexual assaults, verbal abuse, being followed, flashing, and harassment, with only 5% reporting it to the police. This briefing highlights key findings, along with recommendations for policymakers and police forces. New academic research by Dr Caroline Miles and Professor Rosemary Broad brings together existing police data, new original survey research, and audio diaries recorded by women runners.

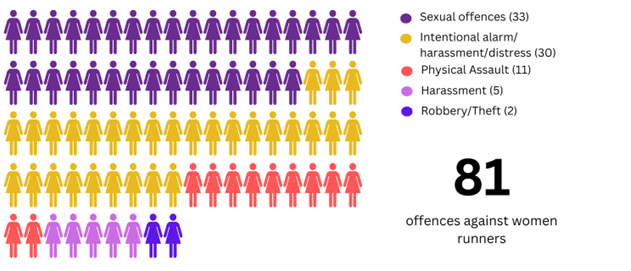

- Over a two-year period in 2021-22, Greater Manchester and Merseyside Police recorded 81 offences involving abuse of women runners.

- 68% of the 498 women survey respondents said they had experiences of being abused whilst out running, but only 5% of these women had reported the abuse to the police.

- 82% of women said they have safety concerns around running and take a multitude of measures to increase their feelings of safety.

Women’s running landscape

A 2021 Runners’ World survey of 2,000 women indicated 60% of women runners had experienced harassment and 25% regularly experienced sexual abuse. Research has illustrated how women change their behaviour based on their perceptions of crime and harassment and under-report incidents due to their everyday experiences of ‘lower-level’ harassment, which can normalise and trivialise these behaviours, increasing the risk of further victimisation.

However, there is a lack of academic research surrounding women’s use of everyday spaces for exercise. There is no criminological research on women runners’ fear of abuse, the impact of their fear and experiences, and attitudes towards reporting abuse to the police.

Our research, in collaboration with Merseyside Police and Greater Manchester Police, addresses the gap in knowledge about women runners’ experiences, fears and perceptions of abuse. We analysed police data, conducted a survey of 498 women, and asked ten women runners to keep audio diaries for one month. Our initials findings were reported on by BBC News (North West), BBC News (online), The Guardian, and Manchester Evening News.

Levels of abuse faced by women runners

Our analysis of police data showed there were 81 offences involving the abuse of women runners recorded by Greater Manchester and Merseyside Police between 1 January 2021 and 31 December 2022. The majority involved sexual offences, followed by offences causing intentional harassment, alarm and distress, and then physical assaults (see Figure 1).

We ran an online survey of 498 women, which showed that 68% said that they had experienced abusive behaviour whilst out running, highlighting the level of under-reporting to the police. For these women, the most common type of abuse experienced was verbal abuse (91%), although a substantial number of women also reported being followed (29%), flashed at (10%), and experiencing ‘other’ forms of abuse (20%), the most common being abuse from men in vehicles. 13 women (4%) said they had been physically assaulted and seven women (2%) had been sexually assaulted whilst out running. No women reported theft crimes, which indicates that the motivation was related to gender rather than economic reasons.

Responses to abuse

Despite the high prevalence of women experiencing abuse whilst out running, 95% of these women had not reported the abuse to the police. A variety of reasons were given for non-reporting, centring around the key themes of a) the abuse of women in public being normalised; b) not perceiving incidents to be criminal offences; and c) low confidence in the police.

‘I did get shouted to by a group of men but they were standing in the pub and I was running past so it didn’t go on for very long as I was out of the way then, I guess because they had a drink and it was semi-late at night about 9 o’clock, they obviously felt comfortable to do that’.

82% of respondents said that they worried about their personal safety whilst out running. What was particularly noteworthy was the magnitude of measures taken by women runners to enhance their feeling of personal safety. Many women reported taking items for safety. Alongside their phones, they held their keys between their fingers as a weapon, used smart watches and apps (Apple watches, Garmin or Strava) to enable family/friends to track them, carried personal alarms (including rape alarms), took dogs and wore lights/reflective clothing. Audio diaries obtained from ten women runners highlight some of the measures taken:

‘When it’s quite early I don’t really like to go into the park, even though it’s light there’s just not a lot of people around so I go on the main road, I only run to a spot in which the houses stop’

‘I do only ever have my music in one ear and I have it quite quiet so that I can still hear what’s going on’

Recommendations

Our findings show that the abuse of women runners is a significantly under-reported form of gender-based violence. Women runners normalise their experiences and take risk management strategies, taking responsibility for their own safety. In light of this research, we recommend:

- Making it easier to report abuse: Engaging with alternative platforms through which women can disclose their experiences, such as using an app to report incidents, rather than directly contacting the police, could improve reporting.

- Improving confidence in the police: Women are reluctant to report incidents of abuse as they fear they will not be taken seriously. Police could do more to encourage women to report incidents (even those perceived as ‘low-level’), and improve their communication with victims about outcomes of investigations.

- Improving police knowledge and action: Making it easier to report abuse and increasing confidence in the police would improve the accuracy of police data in relation to the extent, nature and distribution of incidents. Police could use this intelligence to identify patterns of abuse and detect perpetrators, as in this GMP police operation, which led to a conviction of a serial perpetrator.

- Challenging attitudes: Campaigns, such as Greater Manchester’s ‘Is This Okay’ campaign, have sought to challenge the attitudes and behaviours of boys and men that contribute to gender-based violence. Our research has increased knowledge of women runners’ experiences of abuse, highlighting the need for further work (via education and campaigns) that targets attitudes of men and boys, increases bystander intervention, and shifts the onus away from women to enhance their personal safety.

- Improving access to green space: Mapping the police reported incidents revealed that women runners experience abuse in green spaces, including parks and paths next to waterways; places that are attractive for running. It is essential that women are able to access outdoor spaces for exercise. There is work to be done with urban planners and local authorities to ensure that green spaces are welcoming and safe for all.

- Recognising women runners as a distinct group: The research shows that women often run at quiet times of the day (around work and childcare commitments), in less populated areas, wearing fewer and particular types of clothing, carrying few items, and are more frequently alone. Women runners are therefore a distinct group who frequently experience violence and abuse and need to be represented in the Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) agenda.

Our research shows the range and extent of abuse faced by women runners, and underlines the importance of strengthening the existing national VAWG Strategy and investing in technological solutions that empower women to report abuse.