Martin Yuille, Reader in Biobanking/Co-Director of CIGMR at The University of Manchester argues that it’s time for health policy change course and take prevention seriously.

- The NHS Titanic is lurching toward an iceberg of three big killers: type 2 diabetes, cardio-vascular disease and cancer.

- There are two key components of disease prevention: assessing risk of disease (how big is it) and mitigating that risk (what is done to reduce it).

- A group of health researchers in The University of Manchester’s Centre for Epidemiology proposes a new approach – “Precision Public Health” – which will transform the population’s health and bring these epidemics to an end.

- Precision Public Health is a game-changer for disease prevention. It uses data in electronic NHS health records from primary care (GPs) to stratify populations for risk of obesity, diabetes, cancer.

- As datasets grow, not only will even greater accuracy be achieved, but new insights will emerge on risk and reality in disease processes.

- Health risk-reduction strategy is not working, we need a strategy goes beyond the individual and changes the “system of social habits” to involve our communities, policymakers, businesses, social scientists, health workers and researchers.

The NHS – a victim of its own success

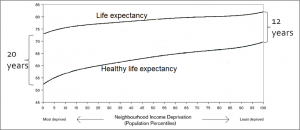

The underlying problem with the NHS – and health systems elsewhere – is that too many people are getting ill and staying ill for too long. The data below show that people spend decades living with poor health that requires interventions.

Figure 1. Healthy life (i.e. disability-free) expectancy and life expectancy at birth by neighbourhood income deprivation (1999-2003) Based on the Marmot Review (p17 Fig 2). Vertical axis indicates life expectancy and healthy life expectancy in years. Horizontal divides neighbourhoods into twenty groups of rising average income.

The only answer to this problem for health systems and the societies in which they are embedded is to prevent avoidable diseases. These diseases consist mainly of Type 2 Diabetes, cardio-vascular disease, cancer. They are today’s three biggest killers. They share a significant risk factor: obesity. There is a global obesity epidemic.

In principle, disease prevention has always been better than cure. But today it needs to be better not just in principle but in practice. The NHS Titanic is lurching toward an iceberg of the three big killers. It’s time to stop rearranging the deckchairs of NHS reform. It’s time to change course and take prevention seriously.

Disease prevention is not about disease as such. It is about risk. The risk of disease. By the time you go to your GP with clinical symptoms, it’s too late. The risk has turned into reality.

There are two key components of disease prevention:

- Assessing risk – how big is it.

- Mitigating risk- what is done to reduce it.

Assessment and mitigation of risk can operate at the population level and at the individual level. Our public health system has for decades operated overwhelmingly at the population level on the three big killers: research is used to quantitate population-level risk and then some form of regulation is promoted where necessary and some form of education about risk is undertaken. This is megaphone Public Health. Action at the individual level has been left to the private sector with its gyms and health food and to the third sector with its fun runs. This strategy has failed to improve population health.

Big data and health

The beginnings of a new approach emerged in 2008 with the launch of the NHS Health Check for cardio-vascular disease (CVD) that prioritises 40-70 year-olds. This aimed to “move from an NHS focussing predominantly on treatment and cure to one that looks first to prevention”. While the NHS Health Check has made a good first stab at risk assessment, it has not delivered on mitigation of risk. Resources have gone into assessment, not mitigation. This is a poor show: it’s like taking your car to a garage for its MOT, discovering your brakes are worn out and then doing nothing.

What is needed is a package with actions affecting both populations and individuals:

- Use Big Data to assess population-wide risks of all major avoidable diseases;

- Prioritise the Health Check for individuals with higher risk defined not only by age;

- Improve the Health Check risk assessment by deploying modern technologies;

- Introduce substantial innovations in mitigation.

Note that the money saved on better prioritisation frees up resources for better mitigation and better mitigation means fewer disease diagnoses. The high per capita cost of treating each of the three killer diseases means that every diagnosis that is avoided frees up resource that can prevent many future diagnoses. Thus there is a snowball effect of cost saving. A virtuous cycle replaces today’s epidemics.

Precision Public Health

A group of health researchers in the University’s Centre for Epidemiology has been working on these ideas. We propose to transform population health first in Manchester and then more widely. The goal is to bring the epidemics to an end. We call our approach “Precision Public Health”.

Others have also called for Precision Public Health approaches but their focus is on assessment alone. We insist that improved mitigation is just as essential. We use the word “precision” to make a contrast with “megaphone” Public Health, to highlight the use of new personalised technologies and to draw a parallel with “Precision Medicine”.

Precision Public Health is a game-changer for disease prevention. By mining the data in electronic NHS health records from primary care (GPs) and secondary care (hospitals), we can stratify populations for risk of obesity, diabetes, cancer, CVD and, of course, for risk of other diseases as well (e.g. depression, dementia, alcoholism). Other sources of data can also be incorporated (e.g. socio-economic data and, potentially, social media data that may give information on social habits).

Higher risk individuals can then be invited for an NHS Health Check. At the check-up, they can be assessed as now – but with added tests based on the new technologies originally developed with Precision Medicine in mind (genetic, epigenetic, proteomic, metabolomic technologies). This will establish quantitative individual risk profiles with a declining reliance on qualitative measures.

Mitigation isn’t working

As datasets grow, not only will even greater accuracy be achieved, but new insights will emerge on risk and reality in disease processes. Follow-up testing would enable individuals to see reductions (or increases) in their risks and would provide an objective measure for researchers on the effectiveness of mitigation strategies.

Mitigation today consists of referral of the individual to a smoking cessation clinic, WeightWatchers, a gym or a swimming pool. That’s it. Maybe a zumba class gets a mention. Maybe attendance costs are subsidised.

This mitigation strategy has not worked: the epidemics in obesity, in diabetes and in cancer have not abated. Changing social habits individual by individual is not, by itself, enough.

A new strategy is needed: mitigation that goes beyond the individual and changes the “system of social habits”, in Nye Bevan’s telling definition of preventive medicine. For Bevan, such change was an ethical imperative because, for him, it defined civilisation. For us, today, such change is simply pragmatic. It is the only way left to us to prevent the three big killer diseases and avert their consequences. Changing the system of social habits needs to involve our communities, policymakers, businesses, social scientists, health workers and researchers – a significantly wider remit than the “health in all policies” concept. Together we all comprise the agents of Precision Public Health.

What is needed to change our system of social habits? Here are a couple of our ideas:

- We need a new profession – a cross between practice nurses and community development workers. We call this new profession “Precision Public Health practise”. A practitioner would assess risk and work initially with the higher-risk individuals on mitigation through linking to community-based organisations to which the individual belongs. The practitioner acts to support change not only in the individual’s social habits but also the social habits of the community in which both are embedded.

- The practitioner’s work in the community would identify change agents – we call them ‘health champions’ – and work with them and their community organisations to support them and to support a ‘health agenda’ for those organisations.

- Government – local and national – should implement the Chief Medical Officer’s recommendation that obesity be placed on the Risk Register (along with flu and terrorism). This would then drive the joined-up government that is essential if public policy – in planning, transport, education, leisure, health – is to be successful in ending the epidemics.

Greater Manchester makes an excellent test bed for these ideas. It has the worst health of any English conurbation – as indicated by life expectancy and obesity data. It has the opportunity for change provided by devolution. It has infrastructure critical to the success of Precision Public Health. It has the reforming zeal of a brand-new political leader in its first elected Mayor.

Acknowledgements

I should like to acknowledge valuable discussions and contributions above all from Prof Bill Ollier (Centre for Integrated Genomic Medical research) and also from, among others, Dr Janine Lamb, Dr Arpana Verma, Prof Ken Muir, Prof Raymond Agius, Prof Mike Donmall, Dr Artitaya Lophatananon who are all colleagues in the FBMH Centre for Epidemiology in the Division of Population Health.